Four Things to Know About Threats to China’s Payment Giants

It’s hard to imagine living in China today without Alipay (支付宝) and WeChat Pay (微信支付). Whether it’s buying goods and services online or even in an old-fashioned shop, getting train or movie tickets, ordering a cab or a takeout, booking a restaurant table, paying utility bills, getting a small loan, sending money to a friend and even donating to charity — almost everything can be paid for from these two now ubiquitous digital wallets with just a few taps on a smartphone or a QR code scan.

From small beginnings providing payment systems for online shopping transactions, WeChat Pay and Alipay have become the goliaths of China’s payment industry and have spread their tentacles into just about everything, even digitizing the Lunar New Year tradition of giving cash-filled red packets. But these closed ecosystems have become an increasing worry to China’s regulators not only because their market power has the potential to snuff out competitors and encourage monopolistic behavior, but also because of the potential risks they could bring to the financial system.

Now, after a decade-long virtually unfettered boom, Alipay and WeChat Pay face sweeping regulatory changes to crimp their dominance, build a more level playing field for competitors and control potential risks. But the rules aren’t just aimed at these two players. They aim to tighten oversight of all nonbank institutions operating in the payments sector, as the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) explained in a statement that accompanied the release of a draft of the “Regulations on Nonbank Payment Institutions” (link in Chinese) on Jan. 20. The draft contains six chapters and 75 articles and will, if approved, give the government and regulators new powers to fight monopolies and rein in dominant players, even going so far as forcing them to divest some of their businesses.

Here are four things to know about the draft rules.

What’s behind the new regulations?

The PBOC laid the groundwork for regulating nonbank payment institutions (NBPIs) back in 2010 (link in Chinese) when e-commerce was taking off in a big way. Alipay, which had been set up by Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. in 2004 and is now owned by its affiliate Ant Group Co. Ltd., was becoming a dominant force in processing payments for customers buying goods and services on its e-commerce platform via their mobile phones and computers. Tencent Holdings Ltd. set up Tenpay in 2005 but its now ubiquitous mobile payments platform WeChat Pay, the biggest competitor to Alipay, didn’t even exist until 2013.

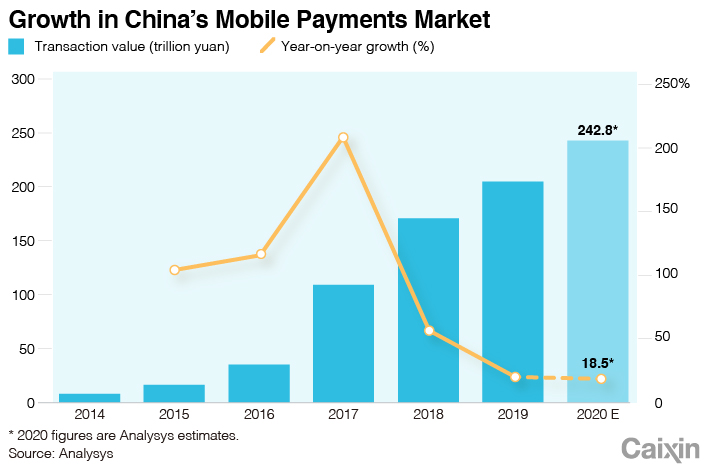

Online payments have exploded over the past decade thanks to the massive growth in e-commerce and consumers’ embrace of smartphones. WeChat Pay and Alipay have built ecosystems around their payment apps which have become springboards that allow users to do just about everything. In 2019, the value of transactions made via mobile payments systems facilitated by NBPIs alone amounted to 204.9 trillion yuan ($31.7 trillion), up from just 8 trillion yuan in 2014, according to data compiled by research firm Analysys. That figure is expected to have risen a further 18.5% in 2020 to 242.8 trillion yuan, the firm said in a report (link in Chinese) released in December.

|

There are now more than 230 licensed NBPIs, also known as third-party payment providers, in China, including GoPay, a company controlled by U.S. fintech giant PayPal Holdings Inc. which became the first foreign company to get a permit in 2019 after buying a majority stake in the firm. But the market is dominated by two giants — Alipay and WeChat Pay. Alipay had 55.39% of the third-party mobile payments market in the second quarter of 2020, while Tenpay, Tencent’s payments business that consists mainly of WeChat Pay, held a 38.47% share, according to data (link in Chinese) from Analysys.

The massive growth in the payments industry over the past decade has made the 2010 regulations seriously outdated.

“In the past few years, the payment service market has developed rapidly,” the PBOC said in a statement accompanying the draft. “There is constant innovation, and risks are complex and changing. Dealing with troubled institutions and their exit from the market has put fresh demands” on regulation, it said.

Regulators are concerned that Alibaba and Tencent are abusing the dominance of their payment platforms, using them to give their other businesses an unfair competitive advantage. Alibaba-owned Taobao, the country’s biggest and dominant online shopping platform, for example, only allows users to pay for goods and services with bank cards or Alipay, shutting out WeChat Pay and other smaller platforms. Likewise, the WeChat social media ecosystem and other platforms owned by Tencent, are not open to Alipay.

The other concern for the financial authorities is the risk of contagion, that if a crisis breaks out at one NBPI, it could quickly spread through the financial system. PBOC Deputy Governor Pan Gongsheng wrote in a Jan. 27 commentary in Britain’s Financial Times newspaper that the fintech sector’s “cross-border, cross-industry and cross-regional nature means that financial risks spread ever faster and wider, with a bigger spillover effect.”

“Network effects mean that fintech competition often leads to ‘winner-takes-all’ outcomes including market monopolies and unfair competition,” Pan wrote.

It’s clear that the authorities intend to fill the regulatory loopholes as the industry develops and ensure that NBPIs stick to their original business.

Caixin has learned from sources with knowledge of the matter that the authorities started work on the new regulations in 2019 and have consulted with relevant government bodies, commercial banks, clearing institutions, industry associations and payment providers, including Alipay and WeChat Pay, as well as other financial technology firms.

What are the highlights of the new regulations?

The PBOC’s draft covers a lot of ground such as compliance with money laundering regulations, how customers’ prepayments and funds need to be managed, and improving corporate governance especially concerning shareholders.

But the main focus and the issue that’s grabbed most of the headlines is competition and monopoly behavior, which the consensus says is a clear shot across the bows of Ant Group and Tencent, who pretty much have a duopoly on third-party payments in China.

One of the key changes involves how NBPIs are supervised and licensed. The current system is based on the type of payment technology and medium, and licenses are issued under three broad categories –– internet payment, prepaid cards, and bank card point-of-sale (POS), according to a report (link in Chinese) by lawyers at Han Kun Law Offices who specialize in cross-border and domestic transactions. But they say that this categorization is outdated. For example, payment using a QR code doesn’t really fit under any of those headings, the report said.

The proposed regulations revamp the license system and re-categorize nonbank payment businesses into two types based on function: those offering stored value payment accounts (储值账户运营业务) and those dealing only with payment transaction processing (支付交易处理业务).

A stored value payments system covers anything that requires opening an account and offering prepayment services. This could include running a prepaid card operation or providing e-wallets, which allow consumers to store and use money digitally, experts have told Caixin. Payment transaction processing covers primarily the processing of payments between customer and vendor with no involvement in stored value payments.

A payment industry veteran told Caixin that the new categorization is a significant regulatory innovation, as the current classification doesn’t fully cover all activities in the third-party payment field. Several sources in the industry have also told Caixin that the proposed change in categorization could signal an overhaul of the licensing system is on the way.

How will the new rules deal with monopolistic practices?

Tackling monopolistic behavior is one of the key aims of the new regulations, part of a broader agenda by the authorities to stamp out monopolies and abuse of market power across a vast swathe of economic activity, not just financial services. Strengthening and improving the enforcement of laws on anti-monopoly and anti-unfair competition are among the priorities highlighted in an action plan to build a “high-standard market system” over the next five years released jointly by the Communist Party and the State Council on Jan. 31.

The PBOC has made it clear that if it finds a monopoly it will break it up, but the devil is in the detail and we don’t have enough at the moment.

Although the draft provides a definition of a monopoly –– by looking primarily at market share –– and outlines intervention measures to tackle monopolistic behavior, it does not define how it will measure market share, whether by number of transactions or by value. Caixin has learned from sources with knowledge of the matter that the central bank is considering publishing more detailed guidelines.

The draft defines a monopoly in third-party payments as any NBPI with a market share of 50% or above in electronic payments, or two institutions that hold a combined two-thirds market share or above, or three that account for at least 75% of the market. The PBOC has previously defined electronic payment (link in Chinese) as including online and mobile payments, and payments made over the phone, at ATMs or via POS terminals in physical transactions.

Any provider that falls within the PBOC’s monopoly definition could be subject to an investigation by the State Council’s antitrust enforcement agency, although the draft didn’t name the agency. If the probe confirms a monopoly exists, the PBOC can then recommend corrective action ranging from suspension of a particular service to a partial breakup of an institution by forcing the divestment of certain operations.

An NBPI with a market share of one-third or two with a combined share of 50% in the nonbank payment market would trigger a warning or a “regulatory interview,” according to the draft.

It’s clear the PBOC has Alipay and WeChat Pay in its sights and wants to break their stranglehold over the mobile payments market and open up access to the dominant ecosystems of Alibaba and Tencent to other players.

Other tech giants such as food delivery service Meituan, ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing Technology Co. Ltd., e-commerce platform and online retailer JD.com Inc., and smartphone-maker Xiaomi Corp. are among rivals that are trying to make a dent in the sector, but they have negligible market shares. State-owned China UnionPay Co. Ltd. — the country’s largest payment and settlement organization, which dominates the bankcard market –– has been trying to break into mobile payments with its QuickPass service since its launch in 2017, but it is still a small player.

The latest to enter the fray is TikTok-owner ByteDance Ltd., which got its payment license through the acquisition of Wuhan Hezhong Epro Technology Co. Ltd. last year. In January, its Chinese short video platform Douyin debuted its eponymous e-wallet Douyin Pay that allows its roughly 600 million daily active users to purchase items from third-party vendors, buy virtual gifts for performers and pay to watch their shows, as well as buy goods during livestreamed e-commerce sessions. But just like Alibaba and Tencent, Douyin is shutting out other major platforms that it increasingly sees as rivals — in October links to Taobao, JD.com and Pinduoduo were banned from its app’s livestreamed e-commerce sessions.

Read more

Cover Story: Why China Faces Handicaps in Antitrust War With Tech Titans

How will the new rules affect NBPIs?

The regulations, in theory, spell bad news for the big players on several fronts.

For starters, any NBPI with a third-party payments license will be required to undergo a “comprehensive assessment” every year rather than having their permit renewed every five years, as the current regulations require. Institutions that have a license will be given a year to make any necessary adjustments and the PBOC will have the power to temporarily halt an institution’s business or even suspend its payment license, if it fails to comply with the draft rules.

The PBOC also appears determined to finally stop NBPIs operating beyond their licensed payments business. Article 25 of the draft aims to prevent them from moving into other finance-related businesses such as lending.

E-wallets that store money digitally have been a port of entry for NBPIs to move into other potentially more lucrative areas such as consumer lending, as Ant Group did with its Huabei (花呗) and Jiebei (借呗) products, which offer unsecured loans to customers.

Read more

In Depth: Want a Loan? Forget the Bank, China’s Tech Giants Are at Your Service

In 2015, the PBOC published measures (link in Chinese) — which took effect in July 2016 — that banned third-party payment providers from operating other financial services including securities, insurance, lending and wealth management. But in reality, the ban has been ineffective. Ant Group, for example, isn’t allowed to embed Jiebei and Huabei into its Alipay wallet but nevertheless they are still there, some industry insiders said.

But because of the fragmented nature of the regulatory system, outdated rules and relatively lax supervision of fintech companies, it was difficult for the authorities to have sufficient oversight and control of these multi-faceted groups that have interconnected products and engage in cross-selling within their ecosystem.

The financial sector has been hit by a series of scandals over the past few years where controlling or major shareholders have used their companies as their personal ATMs to fund reckless expansion –– Anbang Insurance Group Co. Ltd. and Baoshang Bank Co. Ltd. are just two examples. Regulators have been working hard to stamp out this behavior which they see as a potential risk to financial stability, imposing stricter conditions on who can become a shareholder and on what they can do. This draft applies similar regulations to NBPIs. The draft stipulates that any organization can only hold a stake exceeding 10% in one NBPI. An actual controller can only control one payment institution.

This could potentially impact companies that hold two or more payment licenses. For example, aviation-to-insurance conglomerate HNA Group Co. Ltd., Ping An Insurance (Group) Co. of China Ltd. and retailer Suning Holdings Group Co. Ltd. all hold two or more such licenses, and they may need to make adjustments when the new regulations are implemented. UnionPay, however, may be hit hardest — it is the actual controller of 10 NBPIs.

Read More

Reg Watch No. 2: Bringing China’s Wayward Fintech Firms Back Into Line

June Deng contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Timmy Shen (hongmingshen@caixin.com) and editor Nerys Avery (nerysavery@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

- GALLERY

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR