In Depth: Should China’s Central Bank Buy Treasury Bonds?

As countries scramble to keep the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic from devastating their economies, central banks are taking unprecedented easing measures, including cutting rates and purchasing corporate debt and government bonds.

The U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan are all buying government bonds as they have no or little room to further cut interest rates. Now China’s policymakers are in a heated debate over whether to follow suit. But China’s central bank is banned from directly buying government bonds, and opponents worry that such direct monetization of a fiscal deficit could lead to higher inflation, currency depreciation, and the loss of part of the central bank’s monetary policy independence.

The debate was set off by Liu Shangxi, president of the Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences, a Ministry of Finance-affiliated think tank. At a forum last month, he proposed the sale of as much as 5 trillion yuan ($700.5 billion) of special bonds to stimulate the economy. He suggested that the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) buy the bonds at zero interest and then sell them to commercial banks at a later date.

“In the face of the unprecedented impact and challenges [of the pandemic], unprecedented policies are needed to match,” he said.

Borrow money vs. print money

This is not the first time the idea of monetary financing of government fiscal plans was floated. But this time, amid the massive impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the discussion has become even more urgent, and policymakers have more at stake in ensuring the effectiveness of such policies as well as avoiding any sequels.

Coordinating fiscal and monetary policy now requires unprecedented attention, and scholars and policymakers should study the rational bounds of each policy and any overlaps, Liu Yi, a professor at Peking University, told Caixin. The PBOC and the Finance Ministry should establish ministry-level coordination to facilitate more effective governance, she said.

Many scholars have publicly voiced opposition to such a move. Proposing that the PBOC buy government debt directly would essentially be asking the central bank to “print money” to finance the deficit rather than borrowing money by issuing bonds, said Ma Jun, director of the Center for Finance and Development at Tsinghua University and a member of the PBOC’s monetary policy committee.

Borrowing money and printing money could have significantly different long-term effects on the macro economy, fiscal sustainability and financial stability, Ma wrote in an opinion article posted on the Financial News, a newspaper run by the PBOC. Doing so would also mean “giving up the last line of defense on restraining government fiscal behavior,” he said.

Lu Ting, Nomura’s chief China economist, is a supporter of Liu’s proposal. But he emphasized that only under critical conditions should such an extraordinary measure be used, and even then it should be restrained.

|

PBOC vs. Finance Ministry

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the PBOC has been the main force responding in support of economic activity and helping companies recover from the commercial disruptions, including lowering interest rates, injecting liquidity through open market operations and cutting banks’ reserve requirement ratio.

The central bank has also provided 1.8 trillion yuan of cheap funds to banks, encouraging them to make low-interest loans to struggling companies hit hard by the epidemic.

Zhou Xiaochuan, a former PBOC governor, recently said the central bank’s monetary policy has generally been timely and effective.

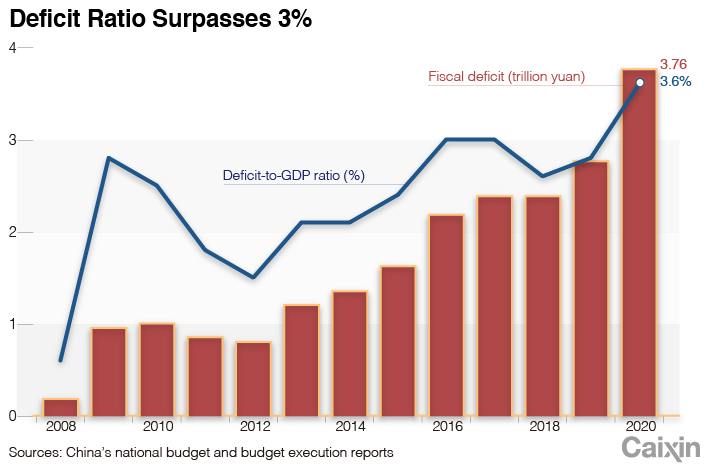

Meanwhile, fiscal response has been lagging. In the early stage, the main fiscal action was tax cuts for some industries. Although a meeting of the Politburo of the Communist Party March 27 proposed the issuance of special bonds, the proposal wasn’t approval until last Friday at the annual session of the National People’s Congress (NPC), the country’s top legislature. Compared with the central bank’s monetary actions, fiscal response has not only been relatively slow but also not as aggressive.

At the NPC session, Premier Li Keqiang announced the issuance of 1 trillion yuan of special treasury bonds to support businesses and regions hit by the outbreak — far below the market expectation of 3 trillion yuan. It is not clear whether the bonds will be monetized by the central bank, but the relatively small size of the issue shows that policymakers are taking a cautious approach to issuing such bonds.

If the central bank doesn’t directly purchase the bonds, large-scale financing through market-oriented issuance would push up interest rates and drain credit from banks, causing the transfer of household savings, Liu said.

Critics argue that direct PBOC purchases of government bonds through the primary market could creating additional money supply while buying only through the secondary market could guarantee the independence of the central bank’s monetary policy.

Former Finance Minister Lou Jiwei, an opponent of direct central bank bond purchases, said such a step would violate the central bank law. The nature of the special bonds and the coordination of monetary and fiscal policy should all follow basic principles, he said.

Other opponents of direct central bank buying, including former Deputy Central Bank Governor Wu Xiaoling, said there is still ample room for fiscal policy to play a role, and there is no lack of demand in the market for government bonds, so the central bank doesn’t need to directly buy bonds in the primary market.

Supporters’ fear that massive bond issuance will push up interest rates is already being realized. The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds climbed to 2.71% from 2.48% at the end of the April.

But opponents said the problem of rising interest rate can be easily solved through technical means. For example, interest rates can be brought down by increasing liquidity or through the local government debt-swap programs, said UB¬S Chief China Econ¬o-mist Wang Tao.

Infrastructure vs. Livelihood

In addition to the PBOC’s role, another concern opponents share is how effective the special bonds could be. China’s fiscal spending has long been criticized as focused more on infrastructure than people’s livelihoods.

According to Premier Li’s annual government work report delivered last Friday, the government’s key efforts this year will be “six protections”: job security, people’s livelihoods, businesses, food and energy security, stable industrial and supply chains, and the functioning of the lower levels of government. The report specifically stressed that all of the proceeds of the 1 trillion yuan of special bonds will be transferred to local governments so that they can support employment, basic needs, and businesses.

No matter who provides the help, whether the central bank or the Finance Ministry, some are worried about how much of the money will actually go to the people and small businesses that were hit hard by the pandemic.

A banker at the microloan department of Jiangsu Changshu Rural Commercial Bank Co. Ltd. said most of the companies eligible for the central government’s Covid-19 loans are medium to large-sized enterprises and very few micro businesses are eligible.

Some government researchers said compared with the banking system, the Finance Ministry is even more lacking in lower-level channels to target the groups in need of help. For example, although the existing social security system can play a great role in helping disadvantaged groups, it’s still difficult to track the large number of migrant workers who are in particular need as a result of the pandemic.

Peking University’s Liu said an institution higher than the central bank and the Finance Ministry should be established to coordinate joint efforts to implement structural monetary and fiscal policies.

Cheng Siwei, Peng Qinqin, Wang Liwei and Wu Hongyuran contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

- GALLERY

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR