Photo Essay: Cram Schools, Prodigies and Free-Range Kids in China’s Capital

Summer vacation once evoked images of children playing outdoors, of ice cream and leisure. But for today’s Chinese schoolchildren it has morphed into a grueling additional semester — a kind of school term outside school.

It’s an extension of many Chinese parents’ educational philosophy as the pressure on children to excel in their school exams increases with fierce competition.

Caixin documented three middle-class families in Beijing, all of whom have parents who are alumni of top Chinese universities. Their parents are eager to train talented children who can escape the public system for an education at an international school.

The ‘prodigy’ method

Concerns over China’s extracurricular cram classes have raged in recent years. In Beijing, the two most famous are held at two schools: the Beijing No. 8 Middle School and the Renda school, which is affiliated with Renmin University. Their classes are experimental accelerated learning programs for gifted children beginning at age 10. They are extremely competitive and can prepare kids to take China’s university entrance exam by just age 15.

Xiao Jing (pseudonym), 10, was a fourth-grade student at a public school in Beijing’s northwestern Haidian district last summer when he was admitted to the Renda school. In 2018, the number of applicants in Beijing topped 18,000. There were 170 spots. As of July 21 this year, the number of applicants for the class had passed 23,000 — a new high.

Xiao Jing failed the first time he took the No. 8 Middle School exam. His mom said that they had prepared for over a year to take the Renda school exam, but his father believes that most of the students in the Renda school’s class were chosen for their talents. While hard work and effort is not wasted, much of the test is difficult to prepare for.

His parents believe he is well suited to such an intense regime. “Early training classes are based on the idea that gifted children can learn faster, and they may be more appropriate to their interests and focus,” his father said. But he noted the classes are still experimental. “It’s a risk and cost for parents,” he said.

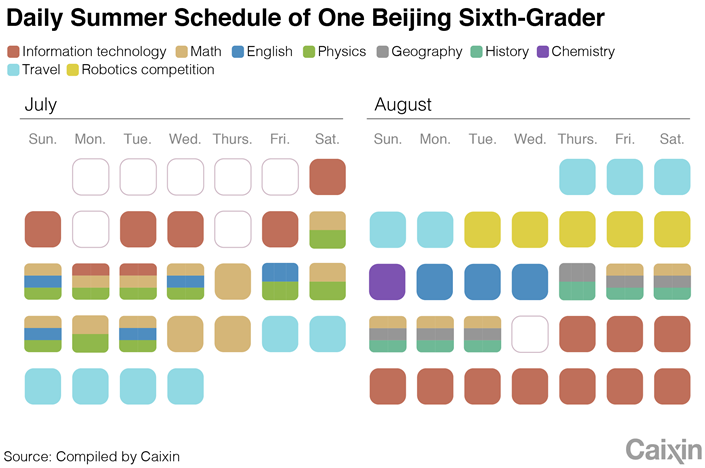

The high intensity training lasts into the summer. Xiao Jing’s parents have planned for their child to focus on his weakest subjects, primarily English. Since Xiao Jing’s dad has a doctorate in computer science, programming lessons are also on the summer syllabus, along with math, physics, and chemistry. Throughout the summer, Xiao Jing’s days end late in the evening. Even during an eight-day stint overseas he doesn’t miss a single online class.

The ‘free-range’ method

Xiao Cha’s (pseudonym) family has a decidedly different approach. He is in fourth grade at an elementary school in one of the central districts of Beijing. There was no pressure for him to get into a competitive training or high school. He watched as his peers threw themselves into extracurricular academic classes. However, his mother Xueli, who holds a master’s degree from Beijing’s prestigious Peking University, adheres to the principles of “happy learning and freedom to grow.”

For the last three years, Xiao Cha’s summer vacations have involved drama lessons, a week of equestrian summer camp, and two weeks traveling overseas and performing charity activities outside of Beijing. In his final school exams he finished in the middle of his class. Xueli did not require him to take extra lessons outside of school but added a one-on-one online English class.

“I don’t want Xiao Cha to grow up and remember his childhood in cram schools,” Xueli says. In her mind, learning is about life experience and cannot be condensed into 12 years of education. Cram schools can teach knowledge, but they cannot teach experience.

Xueli’s husband objected to this method at first, but eventually gave in. He was not opposed to freeing up Xiao Cha’s summers, but worried it would disadvantage him in the long run. Tuition can teach valuable lessons in efficiency, autonomy, and self-discipline, he said.

Despite divergent educational philosophies, Xueli believes their goals are the same. Many parents choose the cram school route — but why should they, she asks. There’s nothing wrong with finding another way.

Somewhere in the middle

Somewhere between the prodigy method and the free-range method sits the approach of most middle class families, who embrace examinations and cram schools.

Shuangshuang and Xintian’s eldest daughter Jiajia is set to start sixth grade, and their youngest daughter Chengcheng will begin third grade after the summer. The two daughters’ summer plans include a camp in the United States, soccer training, cram school classes in the Beijing suburb of Haidian, and learning programming from their dad.

Xintian believes it is important to cultivate her children’s’ independence. “During summer vacation, I hope they show initiative. I’m going to the library to get them library cards. There’s plenty of reading time if they’ve finished their homework on time, even if it’s only 30 minutes,” she said. “They should have some self-determination when it comes to free time, to do things they usually have no time to do.”

Last year, Jiajia transferred from a public school in Haidian to an international school in Shunyi, an affluent district in Beijing’s northeast. Beyond academic pursuits, the international school also offers hockey, and the teachers are very willing to help and are good listeners. In addition, international schools encourage children to ask questions and think critically, read books, and place less importance on results. All of this has made Jiajia more cheerful and confident.

But Xintian still worries about her daughters’ grades. If she wants to return to the result-oriented and obsessed public education system, how will she compete with her peers? How can they find a balance between the “Haidian education” and a “Shunyi education”? Xintian and her husband are taking it as it comes.

“I don’t know if the present education system is suitable for the future world,” Xintian says. “Children have their own pace and interests.” All Xintian can do is slowly guide her children and watch them grow.

|

July 20, 2019 at 10:40 p.m.: Xiao Jing does his homework. There is little difference for him between summer holidays and the academic year — except that during the holiday he gets to travel abroad. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

Parents accompany their children to this extracurricular tutoring class in Beijing. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

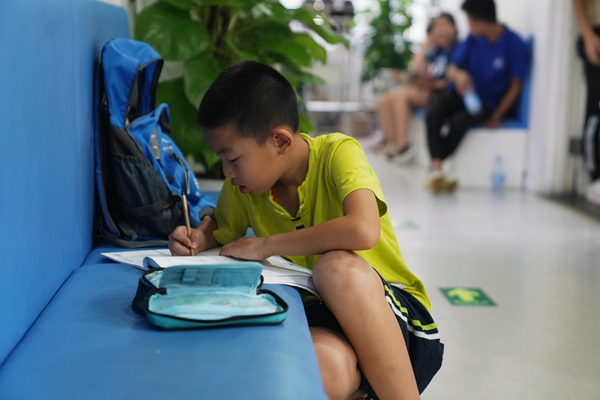

A young student finishes his homework between cram classes. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

Xiao Jing takes photos of mistakes in his homework so he can review them later. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

Xiao Jing enjoys playing with his Lego toys. His room is regularly littered with spare Lego pieces. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

Xiao Cha finishes up his weeklong equestrian camp on July 16. He performed perfectly in the final horse riding show. His mother Xueli says her son’s technique is far better than hers. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

During a class on traditional Chinese comedy performance, the teacher reprimands Xiao Cha and tells him to practice more. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

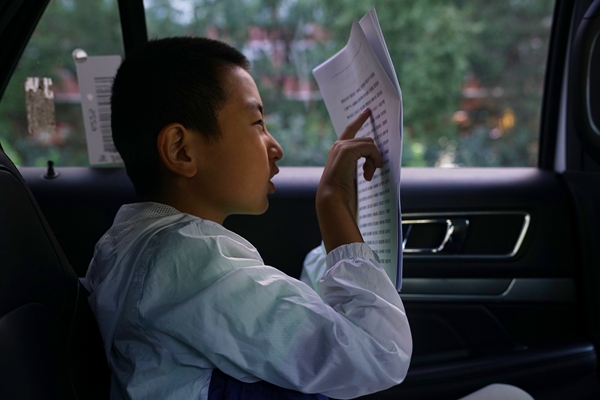

On the way to theater class, Xiao Cha memorizes his lines as his teacher asked. He has been taking the classes for three years. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

Xintian’s youngest daughter practices soccer. She says playing a team sport improves her athleticism and teamwork skills. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

|

Xintian’s eldest daughter is the only girl in her programming class. Her interests are growing increasingly diverse. Photo: Cai Yingli/Caixin |

Contact reporter Ren Qiuyu (qiuyuren@caixin.com)

- GALLERY

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with 财新

Sign in with 财新